Networks of Meaning: Marie-Laure de Decker and the Power of Curatorial Interpretation

Marie-Laure de Decker. Tibesti Tchad,1976-78

The Maison Européenne de la Photographie is dedicating its first major retrospective to Marie-Laure de Decker (1947-2023). What is conceived as the overdue rediscovery of an important photographer also becomes a case study in the power of curatorial interpretation: How are historical photographs reinterpreted to carry today's political messages? And where do the boundaries lie between documentary neutrality and engaged partisanship?

As a viewer encountering Decker's work for the first time, I am entirely dependent on what the exhibition shows and how it contextualizes it—a position that reveals both the possibilities and limitations of interpretation.

The Photographer as Autodidact: From Model to Chronicler

Decker's path was unconventional: at 17, she studied design, discovered photography through exhibitions at Galerie Delpire, and initially worked as a model. In 1971, at age 23, she leaped into the deep end of the Vietnam War without formal photographic training—a remarkable shift from photographed to photographer.

This autodidactic background might explain her later sensitivity to human encounters. Someone who has stood in front of the camera possibly develops a different sense for the dynamics between photographer and subject. Her early Vietnam images already show remarkable technical assurance—exposure, composition, and image construction work precisely, as if she had practiced for years.

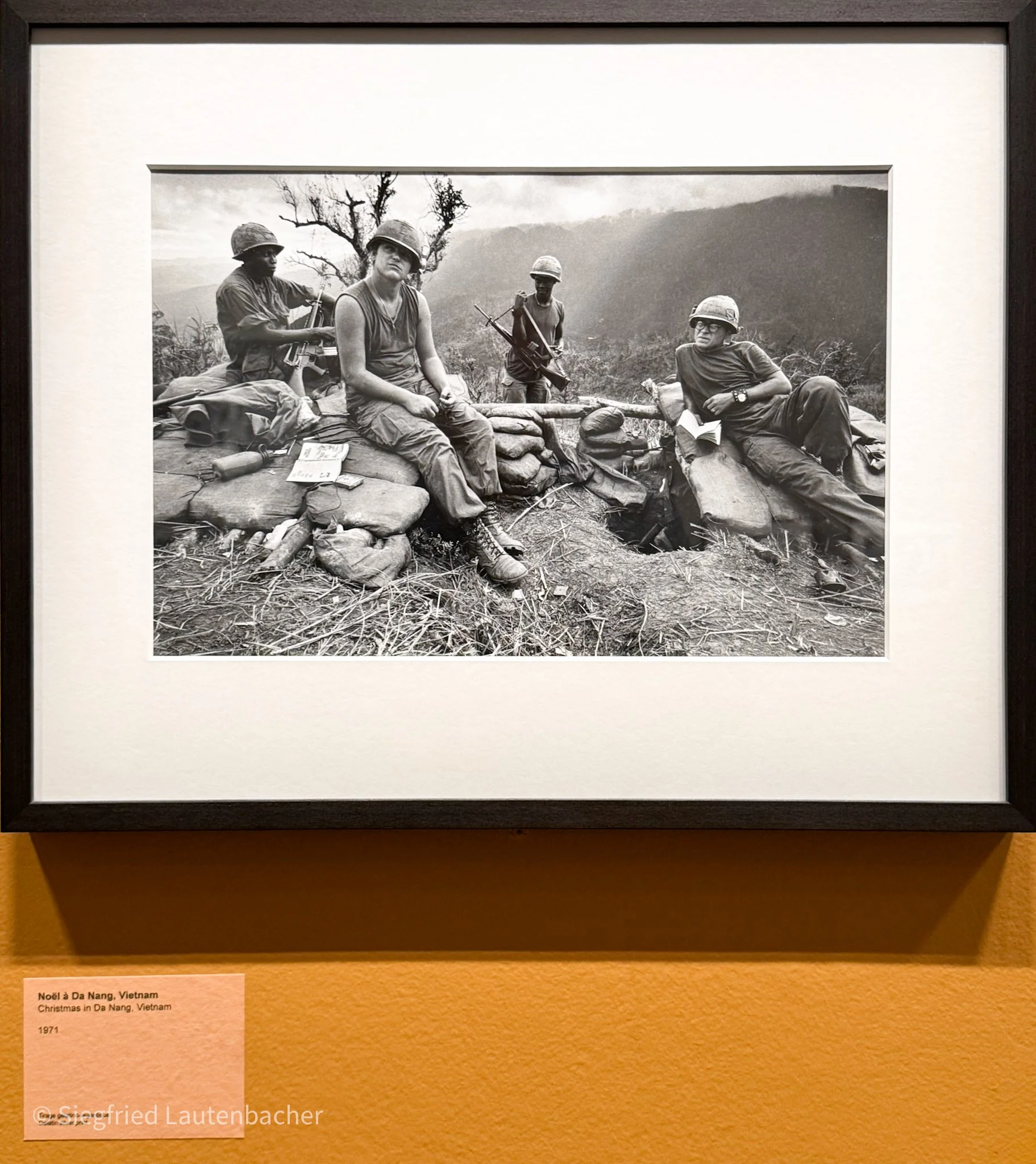

Decker's Vietnam work documents war not as spectacular event but as human experience. Instead of sensational photography, she shows quiet moments between battles: GIs sitting on sandbags, a soldier at the radio, Christmas in Da Nang. These images establish her later credo: photographing people, not events.

Marie-Laure de Decker. Noël à Da Nang Vietnam, 1971

Between Fronts: Yemen and the Art of Differentiation

Her reportage on the reunification of the two Yemens in 1973 shows Decker at the height of her documentary abilities. The portrait series of fighters from North and South Yemen functions like a visual essay on the political and cultural differences between the warring states. Particularly remarkable: her photographs of women in Marxist South Yemen, posing with Kalashnikovs but wearing colourful summer dresses—a perfect image of the contradictions in a society undergoing radical change.

The Power of Exhibition Texts: When History is Retold

This raises the crucial question: whose voice do we hear in the exhibition? Decker's own positions or the interpretations of 2024 curators?

This becomes particularly clear with her photographs from Palestinian refugee camps from 1973. The images show children with dignity and hope in their eyes—documentary photography at its best. The accompanying text, however, transforms them into a political indictment of “ongoing suffering and the denial of fundamental rights of the Palestinian people.” A clear positioning that says more about today's curatorial perspectives than about Decker's intentions at the time.

Marie-Laure de Decker. Camps de réfugiés palestiniens, près d’Amman, Jordanie, 1973

Similarly problematic with her photographs from Mozambique's “re-education camps” in 1979: the texts euphemize forced labour as “vigour of the captives”—but does this interpretation come from Decker or from the exhibition makers? The networks of meaning production between photographer, curators, and visitors remain opaque.

The Chad Dilemma: Documentation or Propaganda?

Her Chad work (1975-78) makes the boundary drawing even more complex. Decker documented the Frolinat (Front de libération nationale du Tchad), a rebel movement that didn't shy away from kidnapping and murder for their cause. She originally came because of the hostage situation involving French archaeologist Françoise Claustre—but stayed to portrait her kidnappers.

Her fighter portraits were created at the explicit request of the rebels: with improvised white sheets as backgrounds, she staged the Frolinat fighters against the rocky landscape of the Tibesti Mountains. “My photos are a testimony to their struggle,” Decker said later. They were meant for survivors and children “to see their fathers at the height of their glory.”

Marie-Laure de Decker. Combattants du Frolinat, Tibesti, Tchad 1976

The images are technically brilliant and aesthetically powerful—but they also function as propaganda for a politically questionable cause. The Frolinat was a fragmented, ideologically vague movement whose later leaders Hissène Habré and Goukouni Oueddei themselves became dictators.

Actor-Network of Meaning Production

What we see in the exhibition is not just Decker's work, but a complex web of photographer, subjects, curators, exhibition texts, and viewers. Each actor in this network influences the meaning of the images. The Frolinat fighters wanted to be portrayed heroically; Decker fulfilled this wish; today's curators interpret this as "engagement"; we as viewers must decide what to make of it.

The problem might lie less in Decker's lack of journalistic training than in the fundamental impossibility of neutral documentation. Every photographic gesture is already an interpretation, every crop a decision, every caption an interpretation.

Observation Without Apparent Agenda

Those works that seem to get by without explicit political message appear particularly impressive. The factory worker in a textile factory in Yemen, scenes from Chinese everyday life (including a cyclist with a pig on his luggage carrier), her photographs from South Africa during apartheid—these images possibly work so well because they seem to show rather than explain.

Her South Africa work emerged in a context of broad international consensus about the illegitimacy of the apartheid system. But here too, the most convincing moments seem to be those where the camera simply documents without commenting—though of course this assessment reflects our subjective reading of the images.

A Contradictory Assessment

Marie-Laure de Decker remains an elusive figure: technically skilled, humanly sensitive, but embedded in a complex network of expectations, interpretations, and retrospective meanings. What might appear to us today as her most convincing work are often those quiet observations of everyday moments—the girl with hand gestures, the cyclist with the pig in China, the children in refugee camps. But this assessment also reflects our preferences, not necessarily Decker's own intentions or the contemporary reception of her work.

The retrospective at MEP deserves recognition for making an important photographer visible. But it also raises questions about the limits of curatorial interpretation: Where does historical contextualization end, where does political instrumentalization begin?

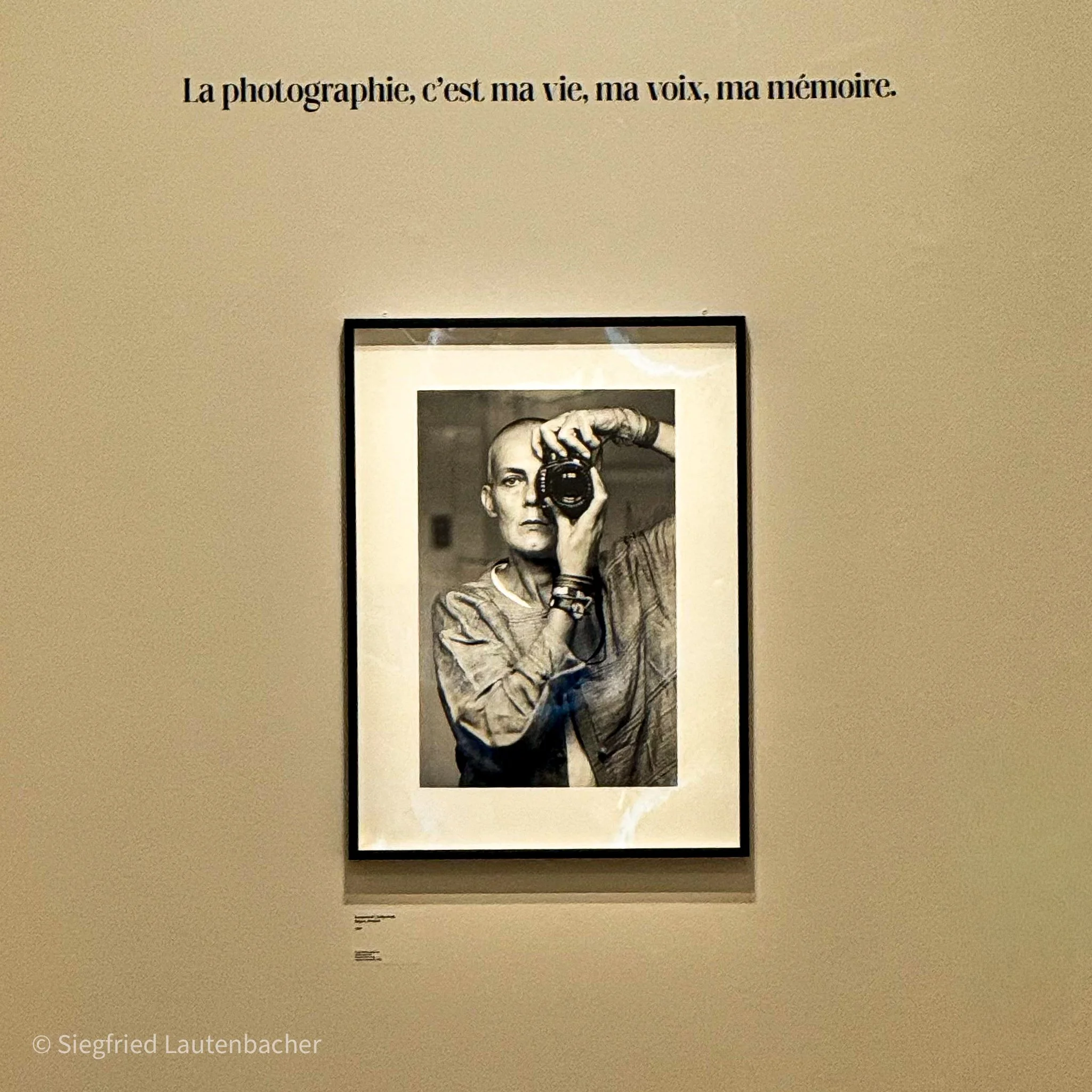

Marie-Laure de Decker. Autoportrait

Perhaps this is the most important lesson from Decker's work: photographs are never just documents, but always carriers of meanings that various actors—photographer, subjects, curators, viewers—invest in them. This doesn't make them less valuable, but it requires us as viewers to maintain critical distance from the narratives constructed around them.

The images themselves remain—as witnesses to human encounters in turbulent times. How we read them is up to us.

The exhibition “Marie-Laure de Decker — L'image comme Engagement” runs until September 28, 2025, at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris.